Here’s an article that’s been a long time coming. On top of my law practice, I’m also a founder of Last Straw Distillery, an award-winning micro-distillery near Toronto, Ontario. I started out as the company’s lawyer, and as with any small business, that role has slowly expanded to a litany of other tasks…. But the lawyer role remains central. I’ve also helped several other alcohol producers through the business startup and licensing process, so the contents of this article are hard-won knowledge. It’s a long read, but it’s a no bullshit assessment of the challenges you’ll face in getting your distillery off the ground.

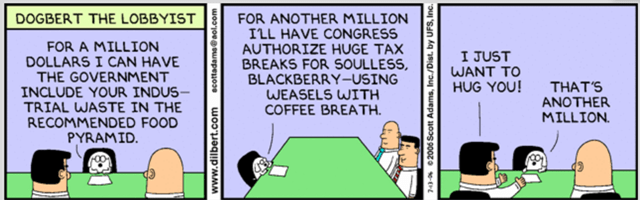

The first thing you need to know about distilling is that it’s heavily regulated. The laws on spirits are even more dense and difficult to navigate than the regulations on beer or wine. This is, of course, because in the inestimable wisdom of successive governments since the end of prohibition, spirits are evil. For some strange reason (probably at the behest of the beer lobby), some Scottish Presbyterian politician in Ontario decided that the ethyl alcohol in hard liquor should be treated differently than the ethyl alcohol in wine and beer.

Much like we’re seeing right now with the legalization of marijuana in Ontario, the laws are written by and for established, well-connected, well-funded big businesses. The time, expense, and expensive advice involved in navigating the system are designed to limit competition. For spirits, the government at the end of prohibition wrote the rules in a way that would make it difficult and expensive to start and run a distillery, and impossible to start on a small scale. As a result, Ontario had only a handful of big distilleries for nearly 80 years. It’s only recently that a few dedicated masochists set out to buck the trend. Through their dedicated efforts, some of the barriers to entry were lowered (slightly), and the Ontario distilling renaissance began.

I’m writing this article as an overview of the major steps involved in starting a distillery in Ontario, Canada. I imagine that most of the steps are mirrored in many other jurisdictions, but the nuances of the regulations will differ. As with any business, you certainly don’t need a lawyer to help you get it started, but a good lawyer will reduce the time from startup to sale, and deal with a lot of the headaches that can come from dealing with five or six different government departments at once.

Let’s get started.

Division of Powers

Booze has the unfortunate distinction of being one of the few market sectors that is regulated by Federal, Provincial, and municipal governments. Technically, municipal governments are a subset of the Province, but practically speaking, it’s another layer you’ll have to deal with.

The Federal government’s primary concern with alcohol regulation is tax. As a luxury item, spirits are subject to Federal tax under the Excise Act. This tax accrues from the moment a drop of alcohol is manufactured, but only becomes payable when the alcohol is sold. More on this later. The Federal government also regulates the production, and labeling of spirits through the Food and Drugs Act and its Regulations, Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act, Consumer Packaging and Labelling Regulations, and the Spirit Drinks Trade Act. Oh, and if you’re thinking about selling your products internationally, the Federal government also regulates and licenses cross-border trade, where a different set of taxes and fees apply, on top of those imposed by the jurisdiction you’re exporting to.

If that bundle of joy isn’t enough for you, the control of liquor is the responsibility of the Province. The Ontario government has created the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario (AGCO) to control the production and sale of spirits in Ontario. The AGCO then created the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), which has an absolute monopoly on spirits sales in Ontario. The AGCO implements government policy on spirits through the Alcohol and Gaming Regulation and Public Protection Act, the Liquor Control Act, and the Liquor License Act. As a manufacturing business, you’re also subject to the rules of the Electrical Safety Authority under the Electricity Act, as well as Ontario’s Building Code and Fire Code.

Lastly, as with any business, spirits producers are subject to the planning and zoning regulations of the municipality you’re in. In some municipalities, there’s a double layer of government – at the regional and town level.

Perhaps the worst part of working through the byzantine maze of regulations are the odd ways in which they interact. As I mentioned, the system was not developed with ease of navigation in mind, and there’s no clear, direct path through them. It’s common for applications to be caught in a Catch-22 of two levels of government refusing to process your application any further without the approval of the other coming first. In my experience, different offices of the same government branch interpret the exact same rules differently (and sometimes incorrectly), and impose different requirements. It takes time and patience to work through these things. Budget at least six months, or more realistically one year to work your way through this stuff. When I say budget, I mean both time and money – as you’ll be spending money on rent for a space you’re not allowed to use while your applications are in progress.

Now that you’re scared, let’s walk you through what it takes to get from idea to open for business.

Form of business

Distilleries can be any form of business, but if you don’t incorporate it, you’re a dumbass. When setting up your corporate structure, two factors will be relevant to the government:

- Who controls the corporation; and

- Who are directors, officers, or holders of at least 10% of any class of shares

Control comes into play in two ways. First, the government wants to know if the applicant is controlled by a company that is already licensed to produce spirits. Each distillery with a Provincial license is allowed one bottle shop at its distillery. An existing manufacturer can invest in starting another distillery, but special permission is required to open a bottle shop at the second distillery. Once you have that special permission, you can sell some products from the first distillery at the second one, but not the other way around. Weird, right?

Secondly, and most importantly, the government wants to know who are directors and officers of the business, and who owns 10% or more of any class of shares of the corporation. Because spirits are evil, the government wants to make sure that the people who own and operate distilleries are at least 19 years old, financially responsible, and of good character. If you own your shares through a holding company, you have to disclose the ownership and management of that holding company, and so on.

In my experience, simplicity in the way you structure the business helps a great deal. The folks reviewing your applications at the CRA and AGCO are not lawyers, and don’t understand the finer points of business ownership. If they see something they don’t understand, they’ll flag it, and get legal advice before proceeding. This, of course, takes time. The more complicated your ownership structure, the longer your application will take.

Zoning & Planning

This is probably the biggest, and most unexpected pain in the ass of the whole process, and where your lawyer will earn their keep. It is absolutely essential that you choose a location that will allow your business model to operate. Because distilleries are still relatively rare when compared to breweries and wineries, most municipalities don’t know how to deal with you. When in doubt, town planners and town councils will err on the side of what will get the municipality the most revenue in development fees. If you ask the municipality whether or not a distillery is allowed, you’ll probably end up paying to play. The only thing you actually need the municipality to do is to sign off on your bottle shop. Some municipalities may require a business license before you can set up shop, but most don’t.

Once you know where you want to start your distillery, and before you start searching for properties, get your lawyer to review that municipality’s planning and zoning bylaws, and provide an opinion. The lawyer’s opinion should tell you what zoning in that municipality allows a distillery to operate. The lawyer will also tell you if a variance or zoning change is required in order to operate. Also, believe it or not, some municipalities still have “dry” (no alcohol allowed) or “damp” (retail sales allowed, but not by the glass) neighbourhoods. The status of the neighbourhood may not prevent you from manufacturing, but it can prevent you from selling through a bottle shop, or an on-site bar. Both the CRA and AGCO will consider whether you’re contravening municipal bylaws, and whether your premises comply with the CRA and AGCO’s regulations. The lawyer’s opinion is super valuable in demonstrating that you’ve ticked all of the boxes.

Lastly, before you sign your lease or buy the property, take a good long look at what’s in the area. If any schools, churches, parks or playgrounds, community centres, or libraries are within a one kilometre radius, you may not be allowed to open a bottle shop or on-site bar.

Building/Fire Code

Once you have a location, you have to build it out. Obviously, all of your construction work must be done in accordance with the Ontario Building Code. Make sure that whoever is doing the work knows and complies with that code. Generally, Building and Fire Codes are dictated by the Province, but enforced by the municipality. Fire inspectors can enter anywhere, at any time, and can shut you down on the spot if you’re not in compliance, so don’t cut corners here.

Distilleries in Ontario are considered “High Hazard Industrial Occupancy” under the Fire Code. That means the building can’t also be used for public assemblies, residences, care facilities like hospitals or clinics, or for detention. If the occupancy load of the building is to be more than 25 people, the building requires emergency planning under the Fire Code. The Fire Code rating (F1) triggers specific requirements in the Building Code for fire-resistant barriers and insulation, emergency exits, and the like. It also triggers requirements in the Electrical Act, requiring the sign-off of an Electrical Safety Authority (ESA) inspector.

ESA sign-off is another odd bird. For all the distilleries I’ve helped through the process, I’ve never seen the same standard applied twice. Each inspector seems to interpret the requirements differently. The inspector’s requirements will play into your build-out – ventilation, type of wiring and electrical fixtures, signs, fire suppression systems, and even separating equipment in different fire-resistant rooms, for example. Find an inspector, and get their direction before you start building. Pass that direction on to the person doing the build out work, and make sure they build to that standard.

Lastly, if you’re looking to open an on-site bar, you’ll need the sign off of the Fire Department. Exits, fire suppression, and signage are all things they’ll look at.

Federal Licensing

Once you’ve got an appropriate space locked down, you can then apply for your Federal licenses. The licenses are tied to the location. You have to occupy/possess the premises before your application will be processed. This means you’re paying rent on a space you can’t use while your applications are being processed – as long as 18 months in some cases.

The Canada Revenue Agency administers the licensing of distilleries under the Excise Tax Act. The licenses are issued for a two year period, and must be renewed. At the time of writing, there are no fees for the federal licenses. There are three key licenses – all of which can be applied for on the same form – which will cover off most things distilleries want to do.

Spirits License

The spirits license is the main one. It’s what permits you to produce or package spirits (beverage alcohol that isn’t wine, and is over 11.9% alcohol – otherwise it’s beer) in Canada, and to possess a still. If you’ve applied for a spirits license, you can possess a still, but can’t operate it. Home distilling is illegal. Without this one, you’re a bootlegger, not a distiller – and you won’t be able to secure any Provincial licenses either.

Excise Warehouse License

If you’re going to be storing spirits – whether in bulk, aging in barrels, or sitting in bottles waiting to be sold – you’ll also need an Excise Warehouse License. This delays the payment of Excise Tax on the spirits until they’re removed from the warehouse.

You will need to post security for the Excise Tax. The amount of security depends primarily on how many litres of absolute alcohol you plan to store in your warehouse. The CRA wants to make sure that even if you go bankrupt, you can still pay your Excise Tax. The minimum is said to be $5,000.00, however the lowest requirement I’ve seen is $10,000.00, and that’s for small distilleries dealing in white spirits – meaning they’re not aging large quantities. If you’re making whisky, rum, brandy, and other aged spirits, plan on posting way more. Security is typically posted by bond (insurance), though you can post negotiable instruments (cash, Canada Savings Bonds, etc) as security as well.

User’s License

The user’s license allows you to transfer bulk alcohol between booze producers of a different type. If you’re planning on buying in bulk alcohol to distill, age, modify, or repackage, you’ll probably need this. I say probably, because different CRA personnel apply the policy differently. You definitely need a user’s license to transfer bulk beer or wine from licensees. You might need a user’s license to buy bulk spirits – such as a neutral grain, or aged whisky for blending. Regardless of what your CRA agent says, some producers won’t transfer bulk spirits to you without seeing your user’s license, so it’s usually a good idea to get this license just in case.

Application

The application process takes anywhere from 3-18 months, depending on your agent, how prepared you are, if there are any issues with the application or the people involved in your business, and how busy the agents are. There are a few parts to the application:

- L63E license application form

- This includes details on directors and officers of the business, and will result in a background check on both criminal and financial sides

- Business plan including:

- Business industry overview;

- Operating plan;

- Human resources plan;

- Financial plan or sources of funds;

- Sale and marketing plan;

Your business plan must include 3 year projections of the litres of absolute alcohol you expect to produce, and the amount of what you produce that will be stored in bulk for aging, compared to what you expect to sell. This is what the CRA will use to calculate your security requirements.

You’ll also need to figure out how you’ll post security for the excise. Most distilleries will buy a bond, rather than posting the cash themselves. It’s a monthly expense, but your capital will be more useful elsewhere. The CRA will require the sealed original bond.

Once you’ve submitted the application, the CRA will get in touch with you pretty quickly to start the process. They’ll schedule a site visit, so they can inspect your facility to ensure it’s suitable (they’re primarily concerned with physical security – if someone steals your spirits, they’re stealing tax dollars too!). You don’t have to be fully built out by this point, but you must at least have the premises and a floor plan.

They’ll also confirm that you’ve ordered your still and instruments for measuring alcohol content. Your instruments must be inspected/calibrated by the CRA to ensure they’re accurate, which involves a fee. They may conduct a second site inspection before granting the license.

Once the license is approved, you’re finally able to produce spirits! Crank that still up, and get to work!

Provincial Licensing

Bet you thought the hard part was over. Well, it’s not. While the CRA licenses will allow you to produce and store alcohol, if you want to sell it in Ontario, you’ll need another set of licenses and authorizations from the Provincial government, which are administered by the AGCO.

The Provincial Manufacturer’s License is what allows you to sell spirits in Ontario. It takes about 1-3 months to process, if all goes smoothly, and costs $2,540.00 for 2 years, or $5,040 for 4 years at the time of writing. The application requires:

- Completed application form

- Business plan – generally the same one that you used for your CRA license will do, plus:

- Floor plans for your facility

- Details on planned sales channels

- If you’ll be buying in mash, low wines, or bulk spirits from other producers

- Municipal authorization form

- Copy of CRA Spirits License

- Lab test results on at least one product

- Copy of business name registration

- Application fee (non-refundable)

The AGCO will schedule a site inspection of your facility. As with the CRA, different agents will focus on different things, and sometimes the agent will waive the site inspection altogether.

Bottle Shop

If you want to operate a retail store on site, then you’ll need a retail store authorization from the AGCO. The AGCO delegates the administration of this to the LCBO. There’s no fee for the application, but you must include:

- Municipal Information for a Retail Store Authorization form

- Site plan detailing the production site and the proposed retail store location

- Floor plan of the proposed retail store including square footage

- If ownership and control of the production site is shared with any other licensed manufacturer – supplementary documentation demonstrating substantial ownership and control of the production site

- A copy of each notification letter (if applicable) sent to any place of religious assembly, schools, public parks and playgrounds, community centers or libraries within 1 km of your proposed store location and copies of any responses/objections

If your bottle shop is approved, then you’ll need to sign a non-negotiable contract with the LCBO about how the bottle shop will be operated, and how you’ll pay the Spirits Tax. One of the most time-consuming parts of this contract is waiting for the LCBO to sign it – as only the President of the LCBO signs them, and does so about once a month. Schedule your grand opening accordingly!

Direct Delivery

If you want to deliver directly to bars & restaurants or to duty free shops, you’ll need separate direct delivery authorizations for each. The process is much the same as for a bottle shop, and results in another contract.

There are also separate licenses to sell spirits by the glass, and to operate an on-site bar or restaurant of your own, but we’ll save those for a future article.

Summary

As you can tell, it’s an awfully long and tedious process to get a distillery from the idea stage into operations. The typical timeline is 6-18 months, based largely on factors outside of your control. In my experience, each agent of a regulator that gets its hands on your application views the requirements differently, so there’s often a fair bit of back and forth involved.

TL;DR? Here’s Mikes’ 9 “Simple” Steps to Starting a Distillery in Ontario

- Incorporate

- Lawyer’s opinion on zoning/planning

- Sign lease

- Submit CRA license application

- Hire ESA inspector, get requirements for buildout

- Build

- Get CRA licenses, get municipal authorization

- Apply for AGCO licenses & authorizations

- Profit

Of course, having someone to turn to who’s been through the process before can help to grease the wheels. I’ve helped several distilleries through the startup process, and I’d be happy to help yours too. Drop me an email, and let’s talk!

Mike Hook

Intrepid Lawyer

https://intrepidlaw.ca

Vincenzo Strati

I know this post is a few months old, but this is the best and most informative collection of details of starting a distillery in Ontario that i’ve seen EVER. As a guy who’s been struggling to open since 2016, I can sure appreciate the effort involved in putting this together. Thanks!!!

intrepidlawyer

Cheers Vincenzo! Glad you found it helpful!

AR

Fantastic read. If I may ask, what is the smallest startup cost for a new distillery in Ontario you’ve seen?

Mike Hook

Thanks! I don’t have that sort of general business information, unfortunately. Your best bet is to reach out to different distilleries operating on the scale you’d like to be at, and get their thoughts.

Taylor

I’ll echo Vincenzo’s sentinment. This article is absolutely phenomenal, well done and thank you for the work!

Mike Hook

Cheers Taylor! Glad you found it useful!

Mike

Wow great work I have been wanting to start rum distillery almost 25 years ago then they told me you had to process 5000 litres in a 24 hr period or something like that I had 2 investors of 1.5 million this is really helpful going to approach them again could you please email [email protected] would definitely use your service! If this takes off