There are a lot of different models available to people to set up their businesses, but one of the most underused is the cooperative model. Frankly, I find it odd that so few startups consider using a co-op, given the shift towards people-centric companies, corporate social responsibility, social enterprise, crowdfunding, and the sharing economy. In many ways, co-ops are ideal for these types of ventures, since the primary aim of a cooperative is to benefit its members. It’s up to the members to decide what “benefit” means, so co-ops are often about more than just maximizing profits.

Perhaps unfamiliarity breeds avoidance. The co-operative corporation is an odd beast, and far less common than corporations, partnerships, and proprietorships. A lot of folks don’t even know the co-op exists as an option. Hell, a lot of business lawyers I know have never touched the things, and just gloss it over in the “other” category when talking about business structures. Its weirdness makes it difficult to understand. Co-ops are a mash-up of business and not-for-profit corporations, with partnership-esque decision-making, which are sort of public companies, and report to a separate branch of government than every other business in Ontario.

It’s high time we blew the dust off the ol’ girl, and maybe you won’t think co-ops are so weird and scary after all. You might even start to think that your business would do well as a co-op, in which case, we should talk.

It’s high time we blew the dust off the ol’ girl, and maybe you won’t think co-ops are so weird and scary after all. You might even start to think that your business would do well as a co-op, in which case, we should talk.

There are a LOT of possible variations in co-ops, so I’ll stick to the basics in this article. The goal is to give you an idea of the broad strokes, and I’ll leave the details for later articles. I’m going to talk about:

- What a co-op is

- Advantages and disadvantages

- Types of ownership

- Types of co-op

- The basics of financing a co-op, and

- The basics of decision making

So what is a Co-op Anyway?

Co-operatives are democratically-run businesses governed by those who use their services – their members. Co-ops generally rely on member participation to make the wheels turn. Members pool their money, goods, or services, have a say in decision making, and share in the profits or losses of the co-op’s business. Members can be human people, corporations, and not-for-profits.

As we’ll see below, a co-op can be set up with shares, like a business corporation; or without, like a not-for-profit. Co-ops with shares can sell them to members and the general public to raise capital. Co-ops without shares may operate as not-for-profits, and apply for charitable status.

As we’ll see below, a co-op can be set up with shares, like a business corporation; or without, like a not-for-profit. Co-ops with shares can sell them to members and the general public to raise capital. Co-ops without shares may operate as not-for-profits, and apply for charitable status.

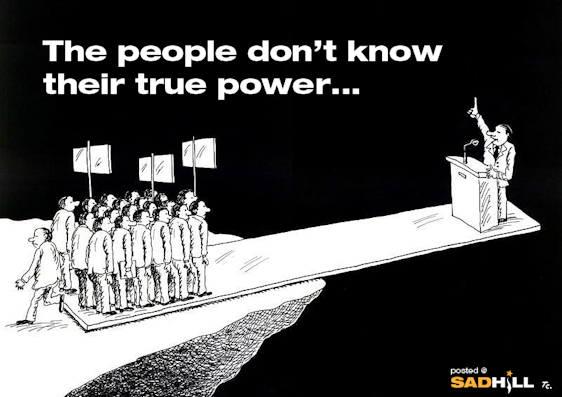

Decision making is one-member, one-vote, so each member has an equal say. Members can be broken down to stakeholder groups, where each group’s votes may be weighted differently, kind of like in a partnership.

Once they reach 35 shareholders or lenders, co-ops become somewhat like a public company, and have to distribute information about the business and its finances to potential investors. The annual financial statements of a co-op must be audited, to ensure that the co-ops accountants are preparing the statements by accounting norms. Ontario co-ops are regulated by the Financial Services Commission of Ontario, rather than the Companies Branch

Advantages

- Egalitarian – while corporations can allow their stakeholders to participate in ownership through stock option plans and the like, such plans are often carefully controlled to prevent those stakeholders from controlling the company.

- Democratic – each member has an equal say.

- Cheaper to set up and run than stock option plans or large partnerships – though the rules governing co-ops can be a bit tedious, many of the rights and responsibilities are written in the law, rather than being custom creations

- Shared resources – members can get access to more and better equipment or facilities, increased negotiating power when buying/selling, shared marketing costs, etc.

- Networking and education – members have access to people who face similar challenges, and make contacts up and down the supply chain.

- Limited liability – a co-op is a “person” in the eyes of the law, which takes on its own liability. Members and shareholders personal assets are protected, and they only stand to lose what they invested.

- Flexibility – co-ops have a huge array of options on goals, structure, financing, decision-making, and services.

- Double or triple bottom line – benefits to the members aren’t limited to a share of the profits.

Disadvantages

- Startup costs – are typically higher than for simple incorporations or partnerships. It takes more legal and accounting work to get ’em off the ground.

- Offering statements are required to raise money – which takes time and money to prepare, and there are ongoing disclosure requirements.

- Annual financial statements must be audited – which adds an extra annual operating expense.

- Decision making can be slow and difficult – especially when there are a lot of members, or stakeholder groups with different interests. Think of how much of a pain in the ass the membership meetings of a condominium can be…

- Unfamiliarity – because there are relatively few co-ops, compared to other business forms, government and foreign entities may have a hard time wrapping their heads around how to deal with you.

Membership Shares, or Members?

You have two options when incorporating a co-op – ownership through shares, similar to a regular ol’ corporation – or control by members, similar to a not-for-profit corporation. Choosing between the two usually comes down to two things:

- Whether the co-op’s purpose is to operate like a business and turn a profit, or to provide a service on a break-even or non-profit basis; and

- How much capital is needed to get started and run the co-op. The greater the need for capital, the more likely it is you’ll lean towards shares.

Consult with your lawyer and accountant before choosing which way you’ll go.

Shares

Shares are just a bunch of rights in the co-op. Most of these rights centre on control (voting), profits (dividends), and ownership (right to a share of the net profit if the business is sold or wound up). Every co-op with share capital must issue at least one type of “membership shares”. Each membership shareholder gets one vote at members’ meetings to do things like electing the directors, setting the rules (bylaws) of the co-op, choosing an auditor, approving annual financial statements, and major business decisions like selling or dissolving the co-op. Different types or membership shares may have slightly different rights.

You also have the option of creating and selling different types of “preference shares” to raise money. Like a regular business corporation, you can get pretty creative with the rights that the preference shareholders have, like priority on dividends, to be bought out or redeemed, to be paid part of the proceeds of liquidation, to receive information, and to receive a portion of the net profits of the co-op each year as a patronage return.

Members

For co-ops without share capital, there are only members, who fill much the same role as membership shareholders, above. The biggest consequence of this type of co-op is that its only financing options are membership fees, loans from members to the co-op, and loans or other debt from outside sources.

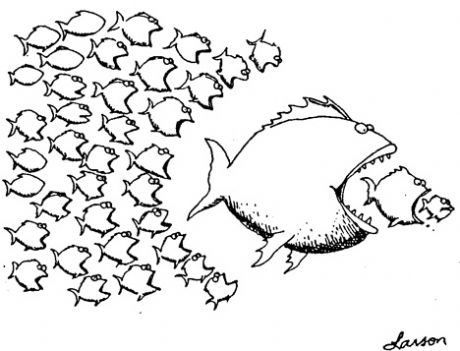

Multi-Stakeholder Co-ops

In these bad boys, members are organized into stakeholder groups, depending on what they contribute to the co-op. Each stakeholder group has certain rights as a group, such as appointing directors to the board, or to receive a lower or higher share of the co-op’s profits.

Types

There are four basic types of co-op in Ontario

- Worker-owned

Exactly what it sounds like. Only workers can be members of the co-op, and at least 75% of employees of the co-op must be members. An example would be Toronto’s Co-op Cabs, where each taxi license holder is a member of the co-op, and gets a share of the net profits of the company rather than revenues from their specific cab.

- Consumer

Businesses, often in retail, which are owned by their customers for their mutual benefit. Resources are pooled to buy in bulk, then the savings are passed on to the members. The most common are credit unions, green energy, insurance, and grocery stores. I’ll lump housing co-ops in here too.

- Producer

Producers of a certain product, or a certain category of goods band together to share common expenses like warehousing, equipment, shipping, and marketing. Most people have seen farmers’ co-ops, which often have warehousing and large equipment, as well as buying farm supplies in bulk. Producer co-ops could work for any business from lumber, to crafts, to booze.

- Multi-stakeholder

Here, many different groups of interests recognize that they’re all in the same boat, and band together for common gain. These groups could include workers, producers, service providers, consumers, and supporters of a certain cause. Health care and social services are common areas for this form. There’s a big push towards sustainable food co-ops right now, bringing together farmers, land owners, seed banks, grocers, and restauranteurs.

Dolla Dolla Bills Y’all

A co-op model can allow a business to take a fundamentally different path than a regular corporation. The directors of corporations are voted in by shareholders to maximize the value of the shares. Co-ops exist for the benefit of their members, which can far broader than simple monetary gain. That’s not to say that a co-op can’t turn a profit. It’s just up to the members as to how far up the priority list profit falls. The rules on how money comes into and flows out of a co-op are different than regular corporations too.

Money In

Besides profits from the sale of goods, the most common fundraising method is membership fees – an annual fee that members must pay to stay members. In most cases, this isn’t a large sum. Co-ops can also charge fees for use to members or the public – like an hourly rate for use of equipment and facilities, or for sales leads they generate for their members.

Debt Financing

As with any business, a co-op can borrow money, known as debt financing, from a variety of sources. Co-ops can, and often do, require their members to loan money to the co-op, which is common in agricultural co-ops where production is cyclical. They need the cash up front to float the year’s operations, and the loans are paid back when the harvest comes in. They can force members to re-invest profits earned from the previous year as member loans as well.

Co-ops can borrow from banks, government, and other private lenders, same as any other business. They can also apply for government grant funding.

Equity Financing

Co-ops with share capital can raise money by selling preference shares. The magic number is 35, meaning that if there will be 35 or more people who own securities (shares and debt) when the sale is done, the co-op has to file an “offering statement” with the Financial Services Commission. This is similar to, but less demanding than, what a corporation must do before “going public”. The goal of the offering statement is to ensure that the investors know what they’re investing in. The exact requirements vary depending on the co-op, but the result must be a full, true, and plain disclosure which answers any reasonable question an investor may have. There are a few exceptions which mean you don’t have to file one for small numbers of investors, and small amounts raised.

Money Out

Aside from paying operating costs, wages, tax, and debt, there are rules about how the profits of the co-op are paid out. What’s left after operating expenses are paid, but before tax, is called the “surplus”.

A co-op can set aside some or all of its surplus to create a “reserve fund” of retained earnings for its future expenses, and it can pay out the surplus through dividends and patronage returns.

Dividends

Dividends are paid out of a co-op’s after tax income. The member or shareholder is taxed on the dividend (not as regular income), meaning some tax credits are available to them.

The maximum dividend allowed on membership shares is the prime lending rate +2% per year. There’s no cap on dividends to preference shareholders, so the rate of dividend is what’s set out in the Articles of the co-op.

Dividends may be paid in more shares of the co-op as well, which allows the business to reinvest the profits, and increase the equity holdings of the shareholders.

Patronage Return

This posh sounding term is the profit share a member is entitled to based on how much business they’ve done with the co-op. This is the main way in which members receive their profits. Patronage returns are paid out of the pre-tax income of the co-op, and are taxed as income for the member.

Different rules apply to different types of co-op, but the way patronage returns are calculated is set out in the bylaws. Worker co-ops, for example, pay patronage returns based on hours worked, or total compensation paid each year. Producer co-ops may account for the relative profits earned from different products contributed to the co-op (a ton of strawberries may turn a higher profit margin than a ton of potatoes. No offence to potatoes.)

Non-members may also be paid a patronage return, so long as the return for non-members is the same or less than what’s paid to members.

Decision Making

As with a corporation, co-ops have three levels of decision-making – members, directors, and officers.

Members

Each member, or membership shareholder, has one vote at meetings of the members. Members have to attend a meeting in order to vote – they can’t send a proxy to vote in their place.

Most votes are decided by a simple majority of votes, after a resolution has been discussed. The key decision members are called upon to make is to elect the board of directors, or removing them if need be. They also approve audited financial statements, and vote on resolutions proposed by members.

Members have a say in other major decisions, which require a 2/3 majority to pass. These include changing the articles of the co-op, adopting new bylaws, and approving the sale or merger of the co-op.

5% of members can call a meeting, or propose member resolutions. 10% of members can force a directors’ meeting to pass a new bylaw or resolution.

Directors

Elected by the members, the directors have a fiduciary duty to run the co-op in the best interests of the members. All directors must be members of the co-op, and there must be at least three directors on the board. The board is responsible to set the strategic direction of the co-op, and appoint the officers to manage its day-to-day affairs. They vote on things like approving new members, budgets, major contracts, and expansion plans.

Officers

Appointed by the directors, officers oversee operations, and supervise the lower-levels of leadership. Officers are employees of the co-op, and except for the President and chair of the board, they don’t have to be members. The duties of the different offices are listed in the Cooperative Corporations Act. Most co-ops will delegate a certain amount of decision-making power to officers, such as the ability to sign contracts up to a certain amount, to hire and fire employees, and to do the co-op’s banking.

Conclusion

So, there you have it, co-ops in a nutshell. This is by no means a complete guide to co-ops in Ontario, but I hope it proves to be a useful starting point. If you’re looking at starting a business or non-profit, take a good, give co-ops due consideration.

There are a ton of good resources out there for information gathering, including a whole series of guides from the FSCO, and the Ontario Co-operative Association that can help you to get started.

As always, I’m happy to help you birth your cooperative business baby. Reach out.

Mike Hook

Intrepid Lawyer

[email protected]

@MikeHookLaw

Lise

Well written article and great layout. You made it easy to read quickly! 🙂